Growth returns to the UK – report February 2011

This report was first published in the Official Catalogue of the Natural Stone Show 2011. To download the pages from the catalogue as PDFs, click here. To go to the Natural Stone Show website, click here.

Last year (2010) ended as it had begun in the British Isles – under several centimetres of snow. That might make for some pretty pictures but it tends to shut down construction sites and bring the UK and Ireland, which just aren’t geared up for snow, to a grinding halt.

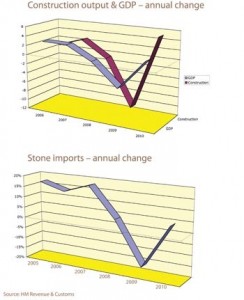

Yet in spite of the problems posed by the weather, both the construction industry in the UK and the economy in general returned to growth in 2010, although the snow did take its inevitable toll on the construction sector with output falling in both the first and fourth quarters of the year.

Nevertheless, the industry performed well in the second and third quarters to grow 5.1% in the year overall, contributing to 1.4% growth in the economy as a whole.

There are no equivalent figures produced in the UK for the stone industry, but with around three-quarters of the stone used in Britain being imported, import figures provide a good snapshot of trends in the industry. And they indicate growth last year was more than 4%.

The fall in construction output in the final quarter of last year could simply mean that work moves forward a month or so, as it did last year.

There are some major developments coming on stream this year and the Olympics are boosting demand for stone in London as hotels, restaurants and public areas such as underground stations prepare for the 2012 games.

Certainly anecdotal evidence from the suppliers of machinery and consumables supports the proposition that the stone industry is gearing up for the opportunities of the year ahead.

There has not been much investment in machines by masonry companies in the UK or Ireland since the world’s bank debt crisis started hitting the rest of the economy in 2008. But according to the companies selling the almost exclusively imported stone processing machinery that is used by the UK stone industry, processing companies started investing again last year to give themselves an edge in an increasingly price sensitive and competitive market place.

That price sensitivity has continued to benefit stone suppliers from the Far East. UK imports from China grew by more than 10% last year and India did even better, up more than 15%. Imports from Asia now account for 58% of stone coming into the UK by value and 68% by volume.

The value of stone imports from Asia first became greater than imports from Europe in 2007 and they have stayed ahead ever since.

Italy is the main European supplier of stone to the UK, but exports to the UK have been hit hard by the fall in the value of sterling, which has increased the price of imports in the UK.

The weakness of sterling has increased the prices of imports from Asia as well as from Europe, but the Chinese and Indians have done more to keep their prices down. Italy has practically conceded the battle on price and is looking to add extra value to the stone it is selling.

You will be able to see some of the ways the Italians are doing that at the Natural Stone Show in the Marmomacc Meets Design feature.

They are using their sophistication in design and production to create intricate stone products rather than the more prosaic polished slab, tiles, hard landscaping and memorials that tend to be bought from Asia.

The Italians have certainly increased the price of the products they are selling to the UK. The average price of stone imports from Italy last year was £990 a tonne, compared with an average price from China of £298 a tonne and from India of £223 a tonne.

That probably explains why stone imports from Italy fell by about 40% last year, according to the figures compiled by HM Revenue & Customs.

While most stone used in the UK for most purposes these days is imported, there remain about 300 active quarries run by about 200 operators producing dimensional stone in the UK.

The UK has practically no marble and there is not much granite being extracted these days because it cannot compete with the prices of Asian imports, but the UK does have a good selection of limestones, sandstones and slates that are used for building, interiors and hard landscaping.

It is in demand by the conservation and repair, maintenance & improvement sectors, but is also used in new build, especially in sensitive areas where planners want traditional materials used and in impressive, prestigious buildings where architects want to make a statement. British limestones, sandstones and slates are also used for interiors, especially, but not exclusively, for floors. The subtle, subdued hues of the stones of the British Isles lend themselves to unpolished finishes making statements of quiet authority.

The dimensional stone production industry in the UK is so small that it is considered too commercially sensitive to produce figures about the industry. However, the producers report reasonable strength of demand for their products.

Walling for housing developments has fallen in line with the collapse of housebuilding in general, but where projects are still going ahead the weakness of sterling is making UK stone more competitive against imports.

There was more British stone than ever before being exhibited at the Natural Stone Show this year.

In Ireland, life is hard.

For many years the Celtic Dragon enjoyed greater growth than the UK and invested heavily in equipment to extract and process its own and imported stones. Stone from the UK often went to Ireland for processing because their level of investment gave processors there a competitive advantage.

But the growth peaked in 2006 and they have been in decline since then. In 2009, construction output was just 39% of what it had been in 2006. And by the third quarter of last year (the latest figures available at the time of writing) it had fallen another 39% year-on-year.

But there are signs that the decline in construction in Ireland has reached the bottom of the curve. The economy in general is, perhaps, improving with the government forecasting 1.7% growth this year.

Construction played a major part in the spectacular growth of Ireland that averaged 6% between 1995 and the end of 2006. In 2006, Ireland’s GDP per capita was greater than America’s.

The country’s population was growing as a result of immigration and for the first time in 100 years exceeded 4million, peaking at nearly 4.5million. The extra people needed more houses to live in and offices and factories to work in. Construction boomed.

Fuelled by strong economic growth, immigration and generous tax incentives and grants from the government, as well as low interest rates and loose credit making borrowing easy, property prices increased more rapidly in Ireland in the decade up to 2006 than in any other economy of the developed world. Between 1996 and 2006 prices more than trebled, even though annual completion rates also trebled to 93,000.

Construction seemed to offer guaranteed, no-risk returns, and speculative building raced on. With the crash, Ireland has been left with more buildings than it needs (an excess of 300,000 houses, 17% of its housing stock, according to a report by University College Dublin in 2010) and prices have collapsed, although there were still nearly 20,000 dwellings built last year.

According to the Permanent TSB/ ESRI house price index almost a decade of price rises have been wiped out since 2006. In the third quarter of 2010 the average price of a house fell a further 14.8%, to Euro198,689, compared with a year earlier. That is 36% down on the peak at the end of 2006.

Stone sales in the UK – report May 2010

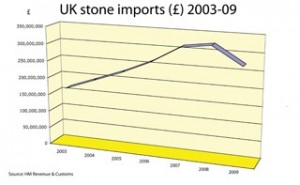

Stone imports to the UK went into decline last year after having held up reasonably well in 2008, when the value of imports was 4% above the 2007 figure. In 2009 the value of imports fell 16%. But that flatters the position. The weakness of stirling (a 15% fall against the Euro and a 25% fall against the US dollar compared with 2007 rates) increased prices through the poor exchange rate. Volumes of stone imports fell by 43%, according to UK government figures.

The UK stone industry got off to a good start in 2008, continuing the exceptional growth that had started in 1996 and continued on a general upwards trend well into double figures ever since. However, as the year progressed the reality of the recession started to bite and after April sales began to fall. The year still showed that increase in the value of imports on 2007 overall. Of course, the rise in prices must also have played its part in curtailing demand.

Imports account for the majority of stone sales in the UK. The indigenous stone quarrying industry is so small that no accurate figures for extraction of dimensional stone from the 300 quarries active in the British Isles (which includes Ireland) exist. Anecdotally, sales of British stone had been pulled along with the general increase in demand for stone in Britain throughout the second half of the 1990s and into the new millennium. Again anecdotally, the fall in demand for stone last year was not as bad for home produced stone as it has been for imports.

Leading the growth in stone sales over the past 15 years have been the interiors market (especially granite and latterly engineered quartz worktops and limestone flooring) and hard landscaping. Both benefited from the falling price of imports thanks to the growth of first India and then China as the source of stone and the falling price of diamond tools to process granite. There have also been a relatively large number of palacial private mansions and country houses built in the British Isles. The top end of the market has held up better than the lower end, which tends to help traditional masonry using indigenous stones because these projects are less price sensative than commercial or public sector projects, where the money being spent has to be accounted for to shareholders or tax payers.

Housebuilding has been particularly severeley hit by the recession as buyers fear further price falls could put them into negative equity. In any case, when people believe the price of anything is going to fall, they are likely to wait until it has fallen to buy it. Even if they want to buy, mortgages have become difficult to secure as the banks demand larger deposits and have increased interest rates on loans. The granite worktop and limestone floor and fireplace market have been particularly badly hit. Many kitchen shops have gone out of business and with them their granite worktop suppliers. Small worktop companies who had put their houses up as collateral for money borrowed to invested in a saw and CNC workcentre were particularly vulnerable. Granite, sandstone and other stones (notably porphyry and some limestone) are the preferred choices of hard landscapers and landscape projects have continued, although imports of stone for this sector fell in 2008 and 2009.

Stone use in every area has grown in the past 15 years. Cities have always used stone, internally and externally, for important buildings. There was also an increasing number of fairly modest houses built with stone walls and archetectural masonry, particularly in those areas of Britain that have traditionally built in stone – the villages of The Cotswolds, Yorkshire, central southern England, Scotland and parts of Wales. Here, planners often insisted on locally produced stone being used to match existing buildings and preserve the vernacular character of such areas. But imports also benefited as all over the country housing developments have incorporated stone fireplaces, and stone floors in reception areas and kitchens in particular, but not exclusively. And nearly all this stone is imported. Latterly, underfloor heating has increased the attraction of stone flooring in living areas. England has always had a lot of conservatories added to houses as a home improvement and, with underfloor heating, the attraction of natural stone flooring in conservatories has increased.

Hotels have been refurbished using marble and polished limestone for bathrooms and floors in reception areas and, in some cases, the rooms. Many offices have used marble, granite, limestone and other decorative stones for floors, wall linings, reception desks, stairs, lift surrounds and other public areas, as well as for cladding for the outer skins of the buildings.

The aesthetic for the natural beauty of stone has pervaded most areas of society in Britain and has been used in ever more interesting and intricate ways as the CNC technology for working stone has improved and become more affordable. Even waterjet cutting, which has not made a big impact on the British market, is beginning to be used for creating intricate patters, especially on flooring and paving.

The past 15 years have been a heady time for the growth of the stone market in the UK that has benefited the whole industry and seen a lot of new companies entering the market.

There is a nervousness in the stone industry now that is curtailing any further investment, especially in machinery for processing stone, sales of which had enjoyed the boom in the industry. Following the May election, the new Government has to address the level of debt in the UK and fiscal and monetary measures taken for that will put further pressure on demand. The country as a whole is nervous and fears a dip back into recession. Until confidence returns, there will not be much of an improvement in sales.

Report from 2005: The rapid growth of the stone industry in the UK that began in the second half of the 1990s has continued into the new millennium, mostly fuelled by imports and much of it associated with the falling price of stone in general and granite in particular.

Since the end of the protracted period of inactivity in the construction industry that lasted for the first half of the 1990s, the stone industry has seen continuous growth.

According to a report* by Symonds Group (now Capita Symonds) for the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister that was published in 2004, the volume of dimensional stone imports had increased by 323% to 1,990,000tonnes by 2001 from a low point in 1996.

The stone industry is notoriously under recorded and difficult to pin down in terms of hard figures, but the limited statistics used by Natural Stone Specialist to track the market have shown continued increases in imports every year since then.

We use 16 categories (commodity codes) from HM Revenue & Customs as an indicator of developments. These figures underestimate the amount and value of stone being imported because they do not include all the dimensional stone that comes into the country. However, they do provide a snapshot of the market that can identify trends using comparable data going back to 1997.

Figures for 2004 show the biggest annual growth yet by volume (46%) although growth by value was only 17%.

This is a familiar trend, even if the divergence is unusually extreme. It reflects the falling prices of stone as well as significant growth in low cost natural stone hard landscaping products, granite worktops and natural stone tiles, mostly limestone or travertine. The lower prices are in no small measure due to ever more stone coming from China and India, esepcially, but also of the falling price of travertine, much of which comes from Turkey.

Both India and China have come from practically nowhere in the international trade of stone 15 years ago to being up there with Italy among the world’s largest now. A major factor in that growth is the low price of their stone.

In the build up to the millennium, city, town and village rejuvenation schemes became much more likely to use natural stone for hard landscaping and the trend has continued since then, helped by the falling prices of granite and sandstone hard landscaping products that no longer appear to be such an expensive alternative to concrete or clay. Perhaps the fact that low cost imported stone is available from familiar as well as new sources (many British quarries, for example, have introduced imported ranges) has also helped.

Imports of setts, kerbs and flagstones rose by 104% by volume in 2004 and 74% by value as customers moved away from the recently popular source of such materials, Portugal (volumes down 21%), to India (up 188%) and China (up 210%). It cannot be coincidental that Portugal’s mean price per tonne for these products was £189 while China’s was £119 and India’s £110. And the prices from China and India both fell in 2004, while Portugal’s increased.

An area of burgeoning growth for imports has been granite for worktops, helped both by fashion and, again, the falling price of granite. However, the prices of granite started falling before India and China had made much impression on the market because of vast improvements in the machinery and diamond tooling to work this hard material. Those developments brought down the cost of processing granite.

But the price of imported polished granite is continuing to fall (value of imports in 2004 up 11%, volumes up 21%). Here, though, a significant factor in the fall of the price was Italy, where the value of imports to the UK fell to £628 a tonne in 2004, more in line with prices from India (£614/tonne) and China (£541/tonne), a fall that is not totally unrelated to the fact that Italy is buying a lot of stone from China and India to process and sell on to the rest of the world.

In general, the price of all imported stone is falling, with the value of imports in all five groups represented on the graphs shown in the PDF of pages that can be downloaded below, growing more slowly than the volume of imports. While that continues, demand for imported stone products might reasonably be expected to continue to grow.

The UK producers, especially the northern sandstone quarriers, received a boost from all those Lottery funded Millennium Projects as the previous century came to an end. City, town and village regeneration schemes consumed a lot of stone. Since then, stone has remained popular for such schemes, although, as noted, the stone used is increasingly likely to be imported.

A resumption of activity in commercial building construction, in particular, in the past eight years has helped UK quarriers, especially where planning authorities want to see materials used that match the materials of existing buildings. This consideration has helped the UK’s limestone and sandstone producers.

Planners also like to see vernacular traditions of stone housebuilding continuing in areas such as the Cotswolds, the Peak District and Yorkshire, which have long traditions of building in stone. The concrete alternatives to stone (sometimes called reconstituted stone) that were used in the 1960s and ’70s have not weathered well and planners now often insist on natural stone being used for house and garden walls. Concrete ‘stone’ is more widely still being used for roofs in spite of both indigenous and imported natural stone alternatives being available.

That local stones are more often being required as a condition of planning permission has, again, helped British limestone and sandstone quarriers, not to mention the suppliers of saws, croppers, tumblers and other machinery used for processing the stone.

Production and use of indigenous stone in the UK is even harder to measure than imports because there are many small firms among the 200 quarry operators that produce stone from 300 active and intermittently active quarries in the British Isles.

The figures produced in the Symonds report are generally considered by operating companies to be an accurate reflection of the volumes of stone produced in Britain, many of the larger companies having co-operated with Symonds in preparing the report for the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

The figures from 1992 to 2001 presented in the report are reproduced on the ‘UK Production’ graph on the downloadable PDF pages below. Official figures collected since then are incomplete. And they have only ever included figures for volumes as the dimensional stone industry is considered so small as to make values commercially sensitive.

While imports continue to satisfy a burgeoning demand for stone interiors in commercial and domestic properties, especially granite worktops, marble bathrooms, stone-tiled wetrooms and limestone floors, British stone is still finding an eager audience. It is used for cladding new builds, for flooring, wall linings, receptions, landscaping and housing. It is worked on the banker into fine masonry and carvings and is always in demand for sensitive conservation work on the country’s finest buildings.