Report July 2013

It is difficult to put figures on the amount or value of dimensional stone extracted in the UK because most companies winning and processing stone are so small their returns to Companies House are totally exempt. The few that are big enough to submit accounts show how small the industry is – Albion Stone, which quarries and mines Portland limestone, the major building stone of London, had sales of just £4.5million in 2012 and MD Michael Poultney said he had enjoyed a particularly good year. Realstone in Derbyshire has 10 quarries and also imports stone. Its turnover in 2011 was £5.1million.

One of the few UK wholesalers that is a PLC is Pisani. Wholesalers sell almost exclusively imported stone, which accounts for the larger part of the UK market. Pisani’s latest accounts (for 2011) show it had a turnover of £16.7million.

Because of the small size of the industry extracting natural dimensional stone in the UK, the figures for production are said to be too sensitive to release. In reality, they are poorly collected. The terminology used in the collection of the data and inaccurate reporting make it impossible to obtain an accurate figure for the amount of dimensional stone produced in the UK. The best that can be done is to look at the commercial and domestic projects using indigenous stone and calculate the amount they are using and the value of it, which is inevitably imprecise.

However, the British producers do generally (and it is anecdotal from the producers themselves, although it is supported by their customers) seem to have suffered less than importers since the collapse of the market in 2009. Building stone in the UK and Ireland comes from about 300 active or occasionally active quarries. Some of them are extremely small scale operations, with extraction being carried out on one or two days a year to produce enough stone to meet demand for the rest of the year. Sometimes the quarry is little more than a hole in the corner of a field from which stone is lifted as needed. Many stones are used in quite small geographical areas, which helps give those areas their distinctive built characters.

Imports of stone (including arrivals, as they are called when they come from within the European Union) still constitute the largest part of the UK stone market by quite some degree, according to the best estimates of those involved in the industry. Most stone used in interiors and much of the stone used for granite plinths and stone cladding is imported. Also, much of the granite and sandstone used in hard landscaping is imported and nearly all stone memorials are now imported, mostly from India and China.

Stone used for the walls of houses is mostly indigenous and has been hit by the decline in house building, although, again, not by as much as might have been imagined as builders have tried to add value to what they have built.

Indigenous stone is also used fairly extensively in hard landscaping (although there is more imported granite and sandstone used). Again, the number of hard landscaping projects has fallen since the end of 2008. Local stone is also widely used for property renovation and repair, maintenance and extensions, and for conservation work on significant properties and monuments in the heritage sector.

Margins on stone have fallen during the downturn, which has been reflected in the reported profitability of extractors, processors and fixers. However, indigenous stone suppliers have not been squeezed as hard as importers as the market for indigenous stone seems to lack price elasticity. As one of the UK quarry companies told Natural Stone Specialist magazine, it dropped its prices in 2010, saw no increase in sales, so put them up again in 2012 and has seen no decrease in sales. Why is demand insensitive to price? One reason is that clients do not generally know the price of stone and when a customer wants indigenous stone the price is not the deciding factor in reaching that decision. Another reason is that the use of indigenous stone is often dictated by planners. To get permission to build houses in desirable areas such as the Cotswolds, builders are often left with no choice but to use local stones.

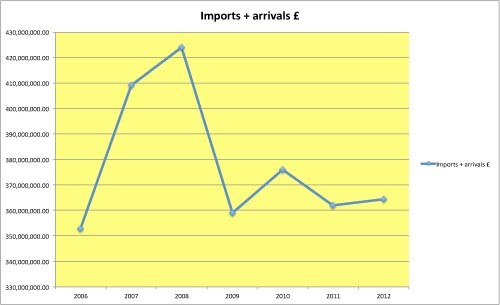

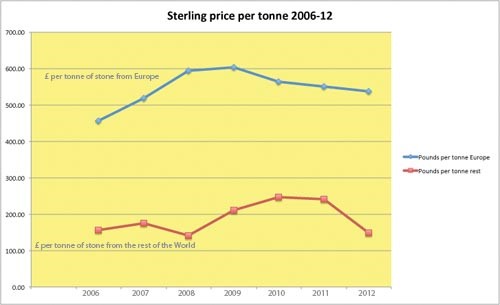

The only presumably reliable figures available about the size of the stone industry in the UK come from HM Revenue & Customs, and they often have peculiarities – although those peculiarities generally disappear over time as the figures are updated. The latest figures, for example, (from which the graphs above were compiled) show a 67% jump in the volume of imports in 2012 while the value went up about 3%. There could have been a big shift to lower value stone, possibly, for example, as the result of the use of a lot of imported stone hard landscaping for the Olympics and perhaps as a result of the Far Eastern companies that have established depots in the UK trading as Stone Yard, KSG (UK), Nile and others. Currency fluctuations also add their complications to comparisons of the value of imports measured in sterling. Nevertheless, experience suggests there could have been an inputting error in the figures that will be corrected in the months ahead. As HMRC tends to be more interested in money than quantities, the value of the imports is usually more reliable than the volume.

According to HMRC, there were £364million worth of dimensional stone imports last year (these figures are amended as the year progresses, but will probably not alter much now). That includes slate (much of which is for roofing) and hard landscaping products. It also includes memorials and excludes some of the stone that will have come into the UK recorded as a product rather than a material (furniture, for example).

If slate and hard landscaping products are removed from the figures (it is not possible to distinguish between stone used for memorials and architectural stone in the figures), the value of the imports left is £265million. Based on Natural Stone Specialist estimates of the value of the market for indigenous stone and the way both indigenous and imported stones are used, that is probably about 77% of the market for architectural and memorial stone (ie excluding slate and hard landscaping – and you can read more about hard landscaping here), leaving the indigenous suppliers with sales of about £80million last year and giving the architectural stone market a total value of around £345million in stone supply.

Once the stone has been sawn, shaped, finished and installed, it is worth considerably more. It is (again) difficult to make an easy calculation about the value added during processing because a piece of stone cropped for walling will have less added value than a polished slab turned into a kitchen worktop, which in turn will have less added value than a 5-tonne block of limestone worked into a Corinthian capital (at least, it appears to have, although when the finished price is divided by the number of hours involved in production, the worktop might look more expensive than the Corinthian capital).

Making an educated guess about the added value, the market at the client end is probably worth about £3,225million. There are around 4,000 companies involved in the various architectural stone markets and another 800 in memorial retailing, making the mean turnover in the sector £670,000 a year.

There were, until 2009, more companies in the kitchen worktop sector, which has suffered particularly badly from the downturn. According to some estimates, about 300 companies, a quarter of the sector, have closed down since the end of 2008 (although some of the directors and employees have subsequently reappeared with new companies, sometimes to the chagrin of their suppliers who have been left holding the debt).

The stone sector grew rapidly after the turn of the millennium on the back of the property bubble but some of the companies that came into the market latterly were too highly geared to be able to survive when demand fell. Others suffered a cash flow crisis when the banks withdrew their support in 2009. Others were able to ride the downturn for a while, but have not been able to survive on the reduced margins as the years have gone by. The slight upturn in stone sales in 2010 has proved to be a dead cat bounce and the market has been basically flat following the bursting of the bubble at the end of 2008. In the middle of 2013, processors going into receivership and leaving bad debts is still a problem for their suppliers.

So far, most of the wholesalers have survived – indeed, new companies have come into the market. Wholesalers of imported stone play a vital role in the distribution chain of the stone industry because there are so many different kinds of stone (and engineered stone alternatives that are also processed by the stone industry) from all over the world. The relatively small size of most processors seldom enables them to gain a price advantage from importing directly. And even if it did, most of them do not want to tie up cash in the amount of stock they need to hold in order to satisfy their customers.

In Ireland, infrastructure is the only light in the construction market as the Government tries to inject some life into economy.

Tough economic times have seen a decline across Ireland’s construction industry, but the infrastructure sector should record positive growth between 2013 and 2017, according to the Timetric report, Construction in Ireland – Key Trends and Opportunities to 2017.

Despite a significant decline in the Irish construction industry – a CAGR (compound annual growth rate – or, in this case, shrinkage rate) of -28.25% between 2008 and 2012 – infrastructure is projected to record a CAGR of 1% between 2013 and 2017. This growth can primarily be attributed to various transport plans and government initiatives that are seeking to stimulate the economy.

Depressed economic conditions as a result of austerity measures are making it difficult for Irish households to repay housing debt. Furthermore, prospective buyers – especially those taking their first steps on to the property ladder – are finding it difficult to secure mortgages without prohibitively large deposits. Consequently,and despite house building being the largest section of the construction market in Ireland (accounting for 34.7% of total construction output in 2012) it was also one of the worst performing between 2008 and 2012, recording a CAGR of -29.37%.

Customer spending in Ireland has been rendered cautious by high unemployment, low wage growth, and a depressed economic outlook. Combined with businesses’ fear of making large investments as a result of government spending cuts and tax hikes, this has had a significantly detrimental effect on Ireland’s commercial construction market, which has recorded the most significant decline of all sectors – a CAGR of -32.93% between 2008 and 2012.

In the industrial sector, uncertainty in the global economy has had a negative effect on Irish exports, affecting the manufacturing industry in particular. This, coupled with the more general economic malaise, saw the Irish industrial construction sector record a CAGR of -31.36% between 2008 and 2012 – the second largest decline of all Irish construction markets.

Although all sectors of Irish construction registered negative growth between 2008 and 2012, a low benchmark interest rate, various transport plans and government initiatives to stimulate the economy are expected to encourage growth in the infrastructure sector between 2013 and 2017.

For further information: Timetric’s report, ‘Construction in Ireland – Key Trends and Opportunities to 2017’ is available at: http://timetric.com/research/report/CN0132MR

Source: Natural Stone Specialist, the monthly magazine for the natural stone industry in the UK and Ireland since 1882